The tl;dr:

Under the NHMRC criteria, most market research, social research and evaluation projects can receive a lower risk review rather than a full HREC review. Few projects meet the criteria for exemption from review.

Introduction

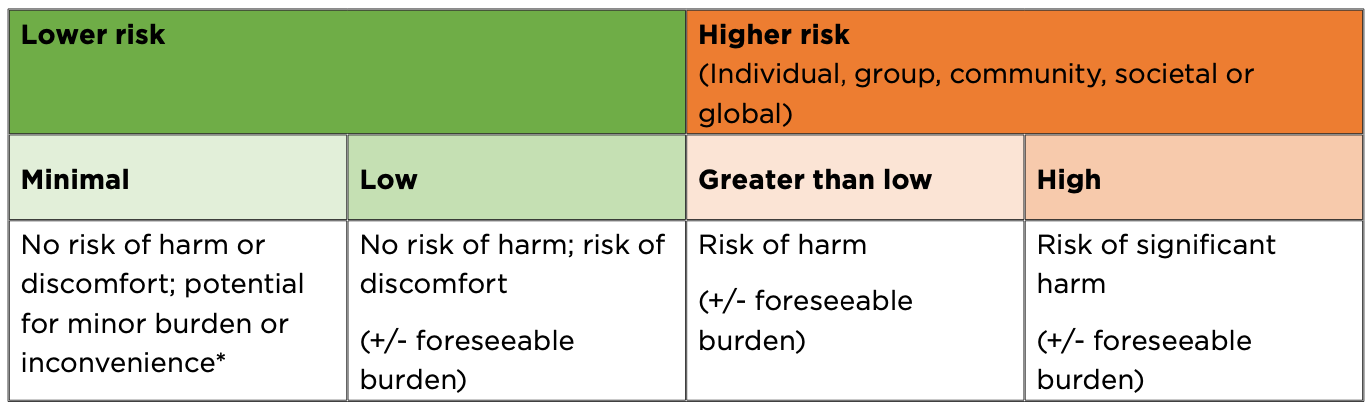

The 2024 and 2025 updates to the National Statement fundamentally changed the ethical review process in Australia. The biggest change in the 2024 update was the move from a three-tier system of risk assessment to a continuum-based model that better reflects the diversity and complexity of scenarios and associated ethical risks. While it is presented as a continuum, the updated statement does identify four general categories of risk:

Under the new system, there is a threshold which separates “higher” and “lower” risk research, delineated by the presence or absence of a risk of harm. In a practical sense, the type of ethical review required differs based on this threshold. If a project or activity is above that threshold, it requires assessment by a full panel of an HREC. Below the threshold, it either goes through a lower risk review process, or it can be exempted (more on this shortly).

The lower risk review process is still an ethical review, but it takes into account that the risk of harm is minimal, and focuses more on ensuring that the activities uphold the principles of the National Statement, and that burdens, inconvenience and risks of discomfort are as low as reasonably achievable in context. Because of this, the reviews are undertaken by an experienced individual or small group, rather than a full HREC. This approach can save both time and money for projects while ensuring the right level of oversight is given.

Why does this matter?

For a long time in the evaluation, market research and social research space, the decision on whether to undertake ethical review was often seen as binary. Either it went before a full HREC, or it was deemed exempt. Not many people knew of or understood the lower risk review process. But more than ever, that process is central to ensuring ethical considerations are identified and managed. This is especially the case with the 2025 update, which takes a more situational and purposive view when it comes to questions of vulnerability, consent, distress and harm. Knowing which ethics review pathway is needed is vital to ensure stakeholder safety and avoid delays in planning and fieldwork.

It’s also important to know that meeting the exemption criteria is not easy. In fact, the bar for exemption is very high, and rightly so. If anything, most research and evaluation requires at least a lower risk review.

Why is this?

Under the National Statement (Section 5.1.17), an activity must meet one or more of the following conditions to be exempted (emphasis added):

- It uses collections of data from which all personal identifiers have been removed prior to provision to the researcher/evaluator and where the researcher/evaluator agrees to not re-identify data and to protect data from re-identification.

- The research is restricted to surveys and public observation without personally identifying information and is highly unlikely to cause distress.

- The activity is conducted as part of educational training.

- Uses information that is publicly available through legislation or regulation (e.g. ABS data or mandatory reporting).

Noting the practical implications of meeting the requirements of point 1, the key condition is the second, which explicitly lists surveys and public observation as activities to which exemptions could apply. Under the 2018 National Statement (Section 5.1.22(b)), the equivalent condition only stated that data be from existing collections of data or be records containing only non-identifiable information about human beings. This meant that in theory, as long as a method resulted in non-identifiable information being recorded (in data or as metadata), it could be exempted from formal review.

Therefore, the use of interview or focus group techniques do not meet the requirement at point 2, and in most cases wouldn’t meet point 1 if the researcher/evaluator is the interviewer or facilitator. This means that projects using these techniques will almost always require a formal ethics review, regardless of the potential risk of harm. And this applies to all interviewed parties, including (for example) those delivering the program.

Even if that bar is met, the NHMRC’s Ethical Considerations in Quality Assurance and Evaluation Activities (2014) add further criteria for exemption, including (among other requirements) that exempted activities cannot:

- Compare cohorts

- Use randomisation or control groups

- Have targeted and separate analysis of minority groups

This rules out a range of common evaluation and research approaches, including all RCTs, all realist evaluations, and most quasi-experimental techniques.

And this is why the lower risk pathway is so important.

In most scenarios a mixed-method evaluation of a program for a general population or a market research study looking at demographic reach and recall is going to present a negligible risk of harm to participants. But there will likely be a potential burden of discomfort or inconvenience of participation, and depending on the magnitude of this you may need to look at things like your incentive structure. However, a full HREC review isn’t the right option.

The lower risk pathway helps to ensure that the review process is matched to the magnitude of potential risk. It still involves a considered and independent analysis by a member of our team, but it ensures that we focus on what’s important in an application, provide independent assessment that the risk of harm is negligible, and make sure that risks of discomfort and inconvenience are managed. That way the principles of research merit and integrity, justice, beneficence, and respect outlined in the National Statement are upheld.